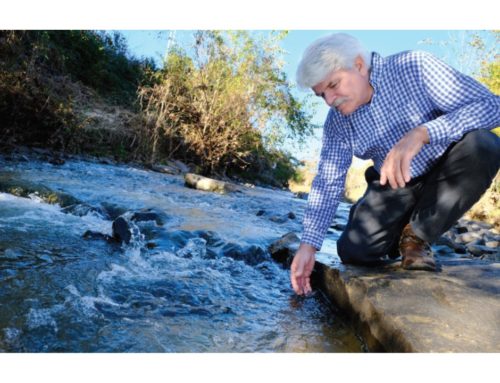

The most remarkable conservationist you might never have heard of spent his long working life in textile mills, fixing looms. Frank (Frankie) Chester lived humbly in a Rowan County mobile home but most days drove to the farm, five miles east of Davidson, which had been in his family for centuries. There he doted on beef cattle although he hated the final steps to sending them to market. Frankie loved to entertain friends under a sprawling white oak.

Until February, Chester also kept a secret: he had donated conservation easements to his 209 acres to the Davidson Lands Conservancy, permanently protecting his land from development. This act of conservation required a substantial sacrifice in the farm’s market value.

It was the most substantial conservation achievement in the 23-year history of the Conservancy. Frankie planned to live out his last years comfortably on the farm.

Those plans died when Frank Chester, at 86 years old, passed away unexpectedly on his beloved farm. A hay delivery driver found Frank deceased outside the barn on April 3.

Frank explained why he decided to leave such a gift of conservation – he did not want to see development of his farmland. To walk through his barnyard, strewn with rusting farm implements, permanently parked tractors and pickups, past the black manure still pocked by cow hooves, to a pasture vibrant with creping buttercups and red clover, is to sense his love of the place.

“The land really seeped into his bones, and I saw that early on,” said Conservancy executive director Dave Cable. “That land was a huge part of his life and he recognized that it was his legacy. He must have told me a hundred times, ‘Dave, I just don’t want to see houses all over this land.’”

Frank had grown up poor on the farm, raised mostly by his grandmother, Bettie Hamilton Chester, and an aunt, Ethel Chester, after his mother died in childbirth. He worked 48 years at Cannon Mills in Kannapolis and took great pride in his skills, daughter Janet Purser said, but had also attended business school and once hoped to join the FBI. He neither smoked, drank nor cursed, and faithfully attended Gilwood Presbyterian Church in Concord. Janet, who lives near the farm, and her son Rodrick, are his only survivors.

Slightly built and reserved around strangers, Chester could also be a tough-talking man, like a “bantam rooster” when needed, Janet said – especially about encroachments at the farm. He was known to sternly invite unwelcome visitors off his land.

His cows revealed Chester’s soft side. He named Button and Oreo, among many others in his 70-cow herd, and mourned those he was forced to sell. “He could stand down in the field and give them the call, “soooook”, a cattle call, and they’d come running like a pack of dogs,” said Clayton Smith, his neighbor, and friend of 25 years.

Bob Johnson, a Davidson farmer who had known Chester most of his life, said the cows were Chester’s pets.

“Frankie was the way that he was, he wasn’t going to change,” Johnson said. “Frankie stuck with it, you know? People tried to get him to change his ways, but he stuck with it. I really admire him for that. He was a true Southern gentleman farmer that’s about all you can say.”

Daughter Janet added to Johnson’s message with, “Dad was a very committed farmer, and loved his land just like his ancestors were.”

The hard work and hazards of farm life didn’t spare the retiree. Chester once fell off his tractor and broke a wrist, and also suffered a concussion after falling from his truck. Simply walking his rolling land, which holds a deep, boulder-lined ravine, was to invite a tumble. Still, well into his 80s, Chester lugged bucket after bucket of feed to his herd several times a week.

Nothing went to waste, even when it should have.

“I can’t be 100% sure,” Smith said, “but I don’t think he ever got rid of anything in his life that had to do with this farm.” Mounds of used baling twine, empty motor oil bottles and cow-mineral buckets litter the place.

After tending his cows, Chester would settle into one of the plastic chairs parked under the big white oak, beside the boarded-up house where he spent part of his childhood. Friends and fans stopped by to chat. He loved Kit Kats, Mountain Dew, Concord’s Independent Tribune newspaper, and word-search puzzles. If the weather was bad, he sat in his car or went to his daughter Janet’s nearby home.

“Little by little, I spent more time with him,” said Janet Andersen, a Conservancy board member who became a dear friend. “And you couldn’t spend just 20 minutes with him – that never happened. It was at least an hour, or four.”

Much of their conversation was about Chester’s early life, she said. In February, the two drove to Raleigh for a farm implement show. “He was like a kid in a candy store,” Andersen said.

Easements protect a vanishing landscape

The Conservancy had begun urging Chester to protect his land under former director Roy Alexander, who died in 2015. Cable, then a volunteer, introduced himself a couple of years later and, sometimes bearing muffins baked by his wife Libby, dropped by regularly. Their friendship, and trust, grew over time.

Farmland is an increasingly scarce commodity in the Charlotte region, where new houses sprout on old fields. Mecklenburg County lost 75% of its farm acreage between 1982 and 2017, according to federal statistics, while Cabarrus County dropped by 23%. North Carolina is the second highest state behind Texas to suffer farmland loss.

As houses went up and traffic intensified around the Chester farm, it became harder to move cows between pastures separated by Davidson Road. Chester relied on friends and neighbors to help, but in recent years had to call Cabarrus County sheriff’s deputies to stop traffic during the maneuver.

In 2020, Chester decided he was ready to protect a 117-acre tract of his farm. He was picky about some details, including retaining the right to mine gold on the property, although there are no legends of gold on the farm, only remnants of old iron plows and tractors. “You never know,” he told Cable.

The Conservancy hired an attorney to represent Chester. Papers were signed on the hood of the 30-year-old Ford Ranger pickup that’s still parked under the oak.

But the ever-private Chester didn’t want anybody else to know about the transaction, broaching his daughter carefully.

“He broke it to me cautiously, pretty much, and I had my concerns,” daughter Janet reported. A retired educator in the Cabarrus County schools, she’s a dedicated child-advocate, gardener and master food preserver. Purser, who is a bit afraid of cows, feels too old to manage a farm.

Would the acreage lose its lower farm-use property tax value if it didn’t continue as an agricultural concern? And would the terms of the conservation easements unduly restrict a farmer who takes over the property? The conservation easements on the farm allow for a wide range of farm uses but permanently prohibit any residential or commercial development on the land.

With her father’s death, Janet feels the need to sell or lease the property, ideally to a dedicated, young farmer, or possibly see it turned into a park or other recreational preserve.

“I don’t feel like that I should keep it, or rather let it be beneficial to others,” she said. “It’s finding a buyer within the parameters of both farm and conservation — where it meets in the middle, that’s where I’m really trying to navigate.”

After telling his daughter about the initial conservation easement, Frank allowed the Conservancy to install boundary signs around the property. He insisted on walking with Conservancy volunteers who do regular stewardship checks. He later said laughingly, “I only fell four times”.

In February, Frank signed an easement protecting his remaining 92 acres. The Davidson Lands Conservancy paid Frank a fraction of the easement’s value made possible by the North Carolina Environmental Enhancement Grant Program, with additional contributions from the Conservancy’s 2018 capital campaign.

He beamed as the Conservancy presented him with a plaque recognizing his achievement and allowed the group to publicize it. “Frankie brought his plaque and showed it to us and he was so happy, so proud,” said his old friend Johnson. The plaque hangs proudly in his daughter Janet’s home.

His death leaves Chester’s beloved farm intact but likely to have new owners. Janet, the bridge to her family land’s past, is now trying to map out its future and provide a beautiful, productive opportunity for others.

“All the families around here handed land down to heirs,” she said. “It’s an interesting concept for some families to think about new blood. How do you move forward in a way that accepts change but retains the family legacy? How do you achieve the vision, a new path that needs to be followed? Frank set the table for the future and the next generation.”